By Monique McIntosh

Love can lead you to the most unexpected places. For mega-collectors Don and Mera Rubell, their decadeslong passion for contemporary art led them to a cluster of warehouses in Allapattah. In 2016, they were just looking for extra storage for their constantly growing number of pieces, a fraction of which were on display at the Rubell Family Collection—the beloved space they opened in 1993 that has helped establish Wynwood as an epicenter of contemporary art.

But love can make you see the beauty in anything, even in an empty depot. “It was just crying out to be a museum,” says Mera of that first tour through the property that swallowed up a full city block. Where others saw loading docks, the couple envisioned what she calls “a space to redefine ourselves.”

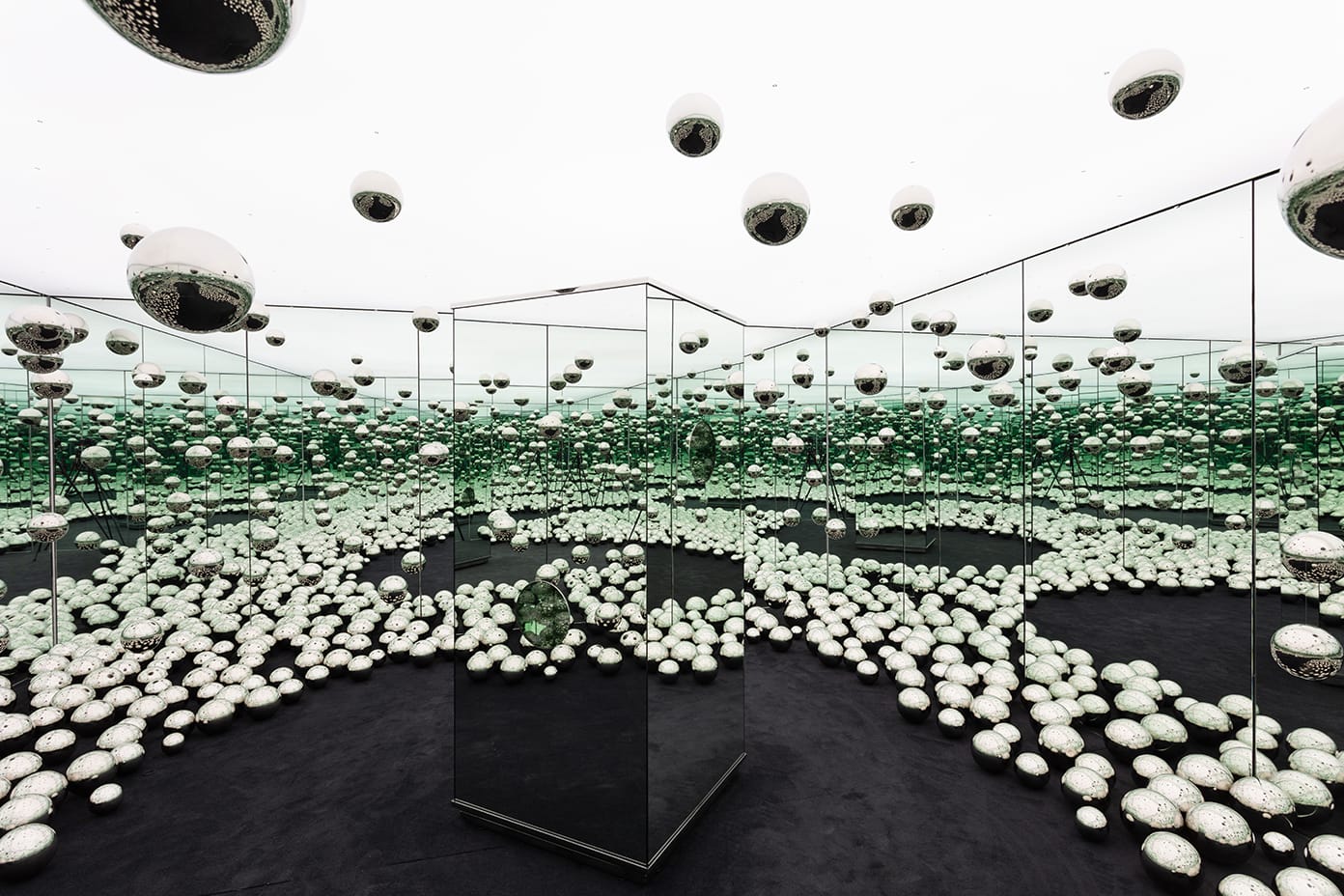

From these daydreams emerged the stunning Rubell Museum, the warehouses reimagined by Selldorf Architects into a remarkable 100,000-square-foot campus. Opened in December in time for the Art Basel Miami Beach season, the new property features 36 galleries to showcase both permanent and curated exhibitions, all pulled exclusively from their collection of over 7,200 works by more than 1,000 artists. Envisioned as a complete escape for art lovers, the space also includes an art research library, as well as Leku, a restaurant featuring Basque-inspired cuisine.

Mera and Don Rubell opened their eponymous museum in December with the intent to dedicate the space for art lovers, complete with an art research library.

The space finally provided enough room to reflect the full scope of the couple’s life’s work as dedicated patrons of contemporary artists over the past 55 years. Renaming their operation from a collection to a museum became an open declaration of the Rubells’ lasting commitment. “We felt people would understand that our objective was to make it as accessible as possible,” Mera says. “Something quite profound happens when you invite the public in. All that you give, the public gives back. It’s a dynamic and rewarding exchange.”

Launching a premier art foundation was not what the couple had in mind when they bought their first piece in the 1960s on a payment plan. The purchase then seemed extravagant for the New York newlyweds, with Don in medical school and Mera working as a teacher. But their love for art has always felt irrevocably entwined with their love for each other. “We still wake up every morning talking about art,” Mera says. “I think finding this common passion has absolutely made for a more dynamic marriage, giving us purpose and meaning.” They also passed on their passion to their children: Jennifer has become an artist in her own right, and Jason joins the family vote on acquiring new pieces.

This spirit of intimacy endured as the couple amassed more work, even more so after they moved to Miami in the 1990s. For the Rubells, each choice remains personal; they are unconcerned with questions of investment or prestige. “For all the looking that we do, it’s still this mystery of infatuation and magic,” says Mera about the selection process.

What remained constant is their unwavering support for undiscovered talent and their lasting relationships with these artists. Unknown then, the names now read like a marquee of contemporary art: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Cindy Sherman, Cecily Brown, Richard Prince and more. Their collection also remains singular for its sheer variety, spanning mediums from video installations to soft sculpture. And while so many contemporary art institutions face necessary criticism for the dramatic gender and ethnic imbalances of their exhibits, the Rubell collection has become a powerful resource due to its diversity. Touring across the country, their groundbreaking exhibitions like “30 Americans,” which showcases pivotal works by African American artists of the last three decades, and “No Man’s Land,” which highlights over 100 female artists across generations, have done much to flesh out conversations about art production today.

From top left: Keith Haring’s Untitled, 1981; Untitled, 1981; Statue of Liberty/Estatua de la libertad, 1982; Untitled, 1982; Untitled, 1981; and Untitled, 1981.

None of this was ever intentional, Mera says. “It started because we came across one talented artist after another, and they’d introduce us to other artists. We were always looking for something to fall in love with.”

These emotional connections still ground the couple’s curatorial vision, though their search has now become digital due to social distancing in response to COVID-19. This transition “is so against the way we experience art,” says Mera mournfully. “We like the physicality of artworks.” But this imposed separation has only reinforced for them the social role of their museum, which reopened in July following health advisory guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In this moment of isolation, such spaces remain vital portals for people to understand each other. “I know art is not more important than life,” Mera says. “But life without art is not as meaningful. Art speaks to the soul of who we are.”

From left to right: Mary Weatherford’s past Sunset, 2015; Carl Andre’s Llano Estacado, Dallas, Texas, 1979; Lucy Dodd’s Guernika, 2014

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2020 Issue.