To all of you,

I wrote this book for you. It’s for everyone. The words on these pages are for our ancestors and those who should not yet be our ancestors but who passed on too soon. I wrote this for you out of a love for liberation and our humanity.

This is the book I wish I would’ve had when I was younger. And it’s the book I will share with my own children. It contains information that I never learned when I was younger and that you will probably not be taught in school.

I wrote these words for you while carrying a heavy heart. It aches for Emmett Till, Tamir Rice, Korryn Gaines, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Bobby Hutton, Antwon Rose Jr., Stephon Clark, Rekia Boyd, Stephen Lawrence, Charleena Lyles, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Aiyana Stanley-Jones and Trayvon Martin, and for all those we honor with hashtags, our tears, our frustration and rage, our exhaustion and the fire to move on.

My optimism has brought me to action and to sharing these words with you because I believe you will help to dismantle racism. We need justice. No one’s name should be memorialized in hashtags.

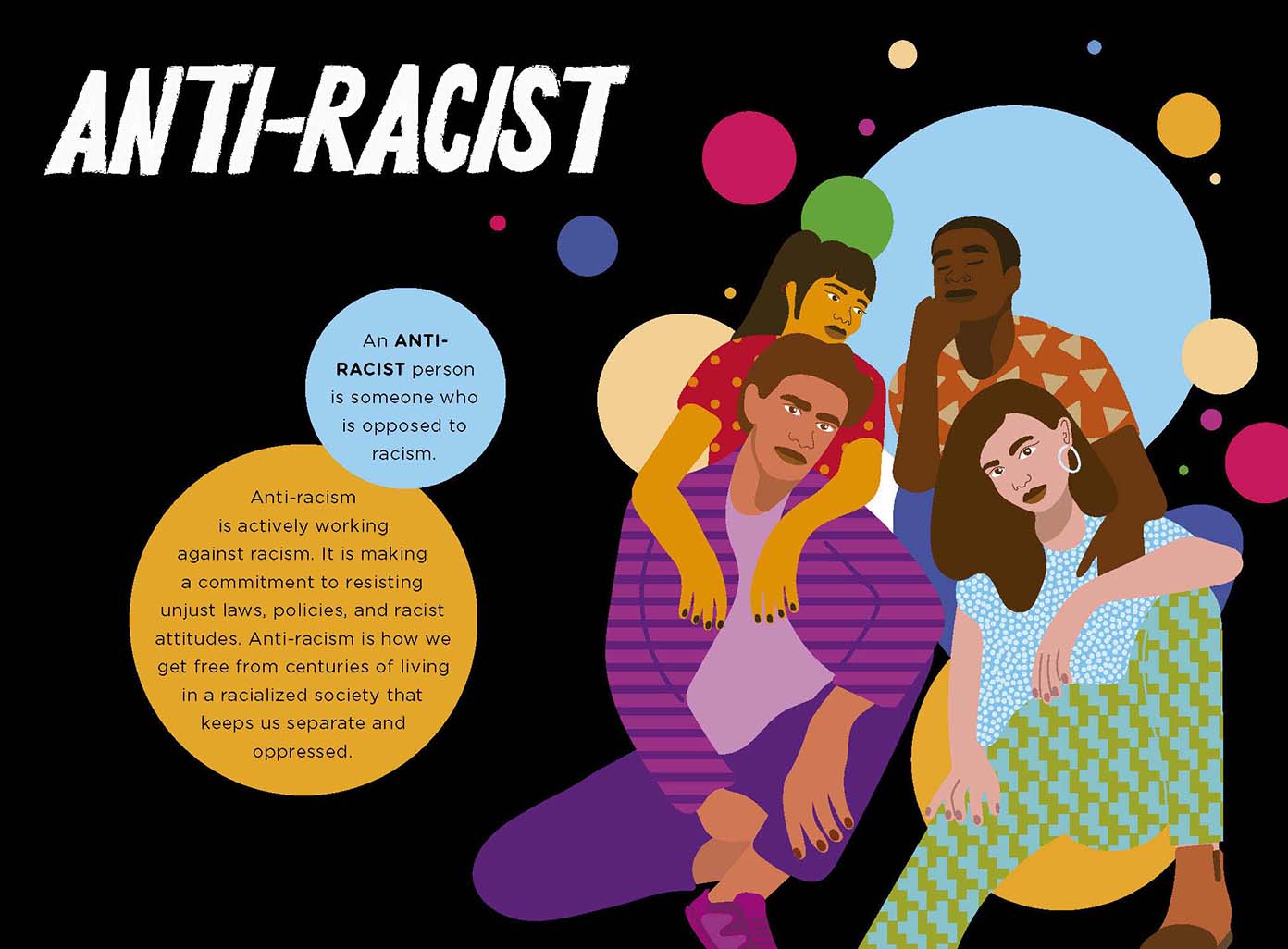

My hope is you will use this book as a way to start your journey in the big work of anti-racism. You are resisting racism and oppression just by opening these pages. You are entering into a consciousness that wakes you up and allows you to see the world in a whole new way.

Can I share a story from my childhood with you? When I was in school, I had a teacher who liked to tell us about all the fun field trips and activities her two blond sons got to do at their school. We did not get to do those kinds of activities. They lived in the suburbs of our city. Their school had a lot more money than ours did. It also had teachers who cared about their students because their students were like them. I do not think my teacher cared about us, mostly Black and Brown children. As a White woman who existed mostly in the dominant culture, she shared her biases with us whether she intended to or not.

The classroom appeared welcoming. Our desks were in groups of four. The windows let in a lot of natural light. The reading corner in the back was inviting, with orange chairs in a semicircle around the small rug. Our teacher read aloud to us every day. My Teacher is an Alien was my favorite.

But she did little things to remind us that she was in charge, that we were powerless, and that some of our lives were worth more and some of our lives were worth less.

One time, she refused to let my classmate use the restroom all morning. His desk was diagonal from mine. He raised his hand (again). Our teacher ignored him until he had an accident that pooled at his feet and our desks. She wasn’t empathetic or sympathetic. She yelled at him. He was the only Latinx boy in our class. He had done nothing wrong.

She tried to humiliate him and showed us all that she had the power to take away our humanity. She decided whether we could use the bathroom, not us. Her actions and words made my classmate feel so small. She showed us that she didn’t care about us.

She tried to humiliate him and showed us all that she had the power to take away our humanity. She decided whether we could use the bathroom, not us. Her actions and words made my classmate feel so small. She showed us that she didn’t care about us.

There was the other time she yelled at my darker-skinned friend because he corrected her on the misinformation she gave us. He and I often corrected our teacher on her misspellings. I remember pointing out to her once that Asia should only have two a’s instead of three. She yelled at him, called him the name of an animal and prefaced it with “Black” and “African.” She said those words with so much anger that they turned ugly in her mouth.

She tried to make us fear my friend. Her words told us there was something wrong with being Black and African. She tried to make us feel like he was less than human. She showed us she didn’t care about us.

My teacher’s prejudice was overt. And she had power. It was easy to see, hear and feel. We could name it. She didn’t like Black and Brown children. She didn’t like our city school. That was obvious to us. We didn’t understand why she was our teacher. Why did she stay at our school? Why was she allowed? Why did none of the other adults care that she was so unkind and unjust toward us, 9- and 10-year-olds? I felt powerless in her classroom because she shared her racist beliefs with us every day in a very negative way.

While some forms of racism are easy to notice and name, others are less overt. You may not be as aware of them right away.

For instance, for as long as I can remember, people (in particular, White people), have asked me, “What are you?” Sometimes it’s followed with, “No, like, what are you?” Throughout my life I’ve answered differently. I am Tiffany. I am human. I am a person. I am Black. I am biracial. When I was a kid, I never knew how to answer because I didn’t know why I was being asked that question. Asking “What are you?” is a common microaggression that folx in the dominant culture ask those in the subordinate culture. Because my race was not clear to some, they felt the need to question me in order to categorize me. They needed to know if I was “one of them.” I even had a friend make a game of guessing my race. Race isn’t a game though; it’s a part of our lives.

___

Adapted from This Book is Anti-Racist: 20 Lessons on How to Wake Up, Take Action and Do the Work, published in 2020 by Frances Lincoln Children’s Books.

Illustrations by Aurelia Durand