By Kat Richter

Photography by Alexander Iziliaev

A typical production of George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker features waltzing snowflakes, frosted windowpanes and a host of characters inspired by the chilly winter delights. “It can be a little hard to relate to,” says Lourdes Lopez, the artistic director of the internationally acclaimed Miami City Ballet. “We don’t get snow down here.”

So, Lopez assembled a team a team of designers, including the late Isabel and Ruben Toledo, to bring her distinctly Miami version of The Nutcracker to life during its performances in December. “Act II is full of pastels,” Lopez says. “I call it the land of sherbet: limes, light greens, pinks and light blues.” If you look closely enough, you can see pineapples and palm trees in the throne from which Marie and the Nutcracker Prince watch the second act. It’s not a Caribbean island per se, but it’s clear that this Land of the Sweets is warm.

Following in an artistic tradition dating back to the Renaissance, The Nutcracker is just one of many ballets in which the music, sets, costumes and, of course, the choreography come together to transport audiences. The careful combination of visual and performing arts has been a hallmark of the concert dance since the first “official” ballet occurred in 1581. King Louis XIV of France, who founded the Académie Royale de Danse in 1661, often performed dressed in brilliant yellows and golds as the literal embodiment of the Sun King.

Production soon modernized. In the early 19th century, technological advances in stagecraft (including trap doors, gas lights and the introduction of the pointe shoe) allowed choreographers to create the illusion of defying gravity and rising from the dead—a hallmark of Romantic era ballets. During the Classical period, Russia dominated with lavish storybook ballets set to the music of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, including The Nutcracker, Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty and Don Quixote. By the start of the 20th century, ballet impresario Serge Diaghilev began commissioning music from Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev and Claude Debussy, costume and set designs from Pablo Picasso, Léon Bakst and Henri Matisse, and choreography from Michel Fokine, Vaslav Nijinsky and finally Balanchine.

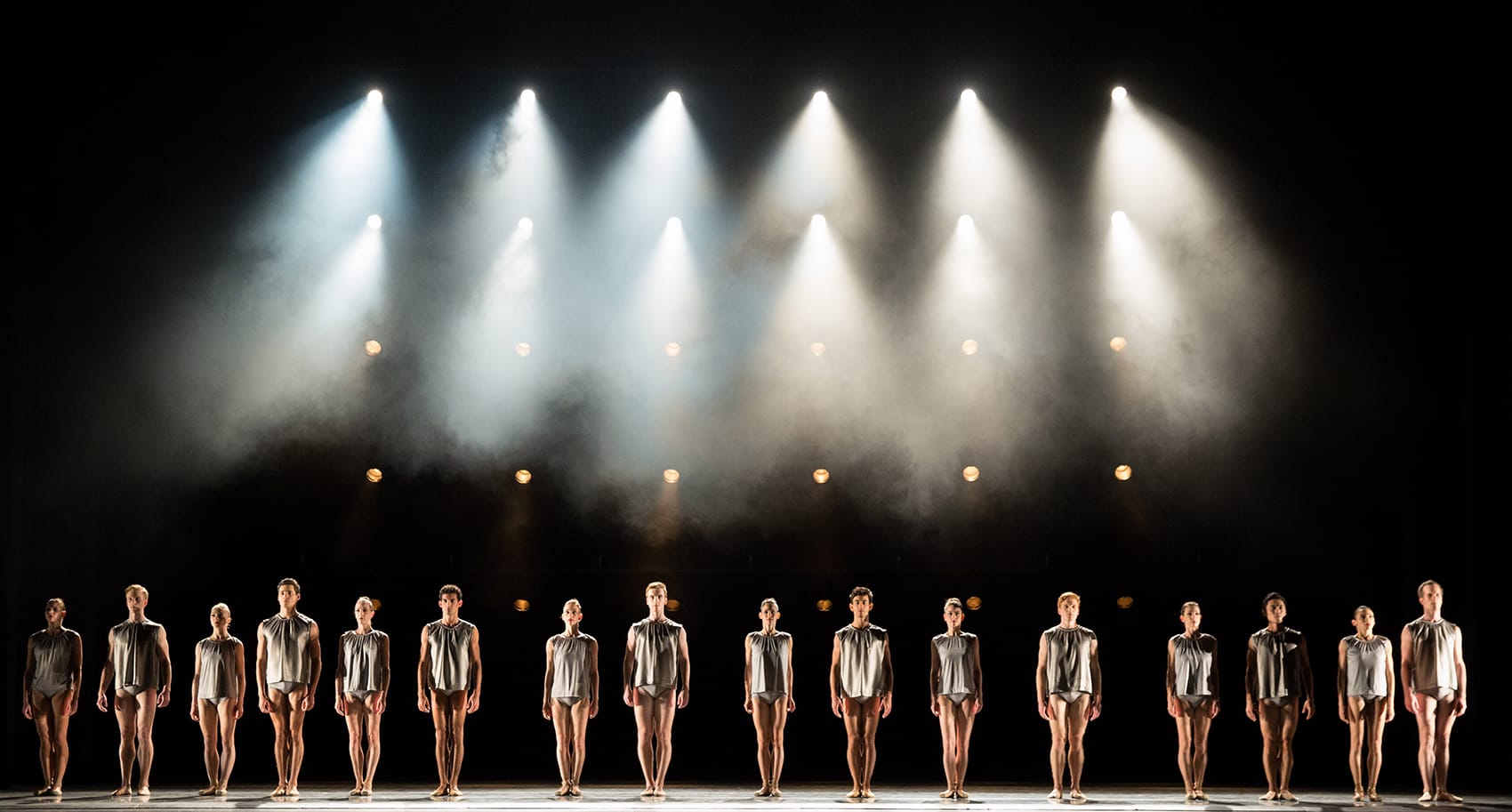

The original Firebird, produced by Diaghilev, premiered at the Paris Opera in 1910. In 1949, Balanchine created his own version for New York City Ballet, a work that “packed the theater” according to Lopez. As a former principal dancer with NYCB, she is thrilled to bring this ballet to Florida in what she says is its first-ever performance outside of the company for which it was created. This February, Lopez and her team will present a 21st century version of The Firebird, complete with design by Anya Klepikov and video projections by Broadway’s Wendall K. Harrington. “It’s a very dark fairytale,” Lopez says. “The prince goes off looking for his fortune and walks into a magical garden of terror. I wanted it to be scary—it should be scary.”

In the 34 years that Miami City Ballet has existed, audience tastes and expectations have changed, Lopez reflects, and so has stagecraft. “Technology has advanced to the point that we are now, and computer graphics—visuals—allow us to transport audiences,” she says.

For example, to create the requisite atmosphere for The Firebird’s “Dance of Death,” Harrington will project skulls and dead soldiers onto the walls of the theater, creating the morose scene.

Besides, she says, “Balanchine had a hole made in the floor of the Koch Theater so that the tree could grow from the bottom up in The Nutcracker. We are always finding new ways of bringing the magic.”

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2019-2020 Issue.